Information exchange continues to be one of the hot topics of Turkish competition law with each passing day. It was long before the Turkish Competition Board ("Board") considered information exchange merely as a facilitating factor in cartel agreements and not a competition law infringement. As currently, the Board has put information exchanges under scrutiny. Following up on the

How did it all start?

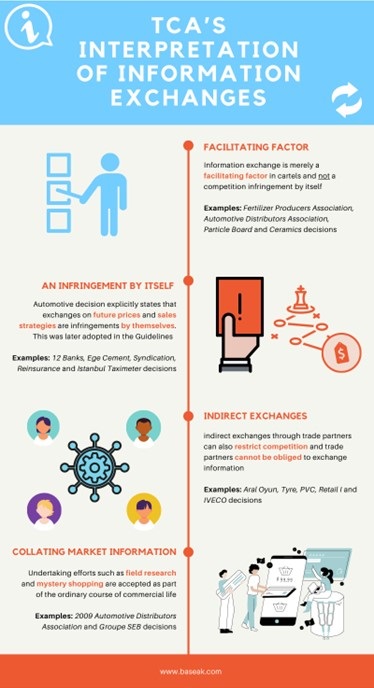

Initially, the Board considered information exchange a facilitating factor in pursuing an existing cartel agreement between competing undertakings. Thus information exchange by itself was not regarded as an infringement under Turkish competition law. Board's ever first analysis of information exchange dates back to 1998, when it introduced structural changes to an information exchange that was to take place between undertakings in the cement industry. In its analysis, the Board argued that information exchanges that allow the identification of its source (i.e., undertaking) would facilitate anti-competitive agreements considering the small number of undertakings operating in the market, the homogeneity of the product, and the high entry barriers in the market1. Similar approaches were adopted in the

When did the information exchange itself fall under TCA's radar?

2011 Automotive decision acts as a turning point in information exchange case law as the Board explicitly declared that information exchanges on future prices and sales strategies would violate Competition Act6. Shortly after, in 2013, the TCA published its Guidelines on Horizontal Cooperation Agreements ("Guideline") and declared as a general rule that information exchange can infringe Turkish competition rules. It also clarified that direct or indirect communication, unilateral exchanges of information, unless declined explicitly, and signalling practices also fall under the scope of the said infringement type. It is noteworthy that both the content and the format of the Guideline highly resembles its

The Guideline elaborated that information exchanges can restrict competition in relevant markets either by-object or by-effect. It also categorized the exchange of forward-looking commercially sensitive information such as price, production, and sales amount as a cartel, or in other words, a by-object infringement, as such exchange of information would aim to determine prices or supply amounts. Board decisions such as 12 Banks8,

On the other hand, for the rest of the information exchanges, the Guideline took into consideration the strategic importance of the information, market structure (transparency), frequency of the exchange, and historic or current nature of the information in the assessment of actual and potential effects of such behavior.

What if the party to the information exchange is not a competitor?

Under Turkish competition law, the party to an information exchange does not act as the deterministic factor in the search for anti-competitive conduct. It is a common understanding that indirect information exchanges through parties at different levels of the supply chain can also lead to restrictions of competition in a particular market. In that regard, the concept known as "hub&spoke" has also found its place in Board decisions. Common factors in the Board's

party to an information exchange does not act as the deterministic factor in the search for anti-competitive conduct. It is a common understanding that indirect information exchanges through parties at different levels of the supply chain can also lead to restrictions of competition in a particular market. In that regard, the concept known as "hub&spoke" has also found its place in Board decisions. Common factors in the Board's

Similarly, in the

The Retail I decision17 again emphasized that the current information obtained through dealers may restrict competition. This time the Board stated that such exchange would not be a restriction on competition by object and yet may trigger anti-competitive effects in the market. Retailers' exchange of product and package-based sales quantity, amount, and price information with suppliers was considered to have the potential to result in anti-competitive effects in the market. However, the suppliers can already access some relevant information through field visits. The case was also significant as it brought forward discussions on information exchanged through independent third parties such as market intelligence agencies. Now, it is up to the opinion letter to be shared by the TCA to clarify which information exchanges are and to what extent they are at stake.

Likewise, in the Istanbul Taximeter decision18, the Board cautiously approached market data collection from trade partners. It evaluated that sharing daily cash register reports disclosing the payment method and the total amount of fares paid may serve to control the prices determined jointly by the taximeter provider companies.

That said, the Board generally allows the collation of information directly from the market through methods such as field research and mystery shopping. For instance, in the 2009

Furthermore, in the Group SEB decision,20 the Board assessed that competitors keeping track of each other's activities is, in fact, in accordance with the ordinary course of commercial life as undertakings determine their commercial strategies in this context. Accordingly, the competitor information obtained from the market through undertakings' means was not considered anti-competitive behavior restricting competition.

Footnotes

1 Şamil Pişmaf, "İktisadi ve Hukuki Açıdan Teşebbüsler Arası Bilgi Değişimi (Information Exchange Between Undertakings in Economic and Legal Perspective)", Series of Competition Experts' Thesis,

2 Board decision dated

3 Board decision dated

4 Board decision dated

5 Board decision dated

6 Competition Act refers to Act No. 4054 on the Protection of Competition.

7

8 Board decision dated

9 Board decision dated

10 Board decision dated

11 Board decision dated

12 Board decision dated

13 Board decision dated

14 Board decision dated

15 Board decision dated

16 Board decision dated

17 Board decision dated

18 Board decision dated

19 Board decision dated

20 Board decision dated

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

Mr Bora Ikiler

Balcioglu Selçuk

Sirketi

Büyükdere Caddesi, Bahar Sokak No.13,

Tel: 2123293030

Fax: 2123293030

E-mail: gcetinkaya@baseak.com

URL: www.baseak.com/

© Mondaq Ltd, 2022 - Tel. +44 (0)20 8544 8300 - http://www.mondaq.com, source