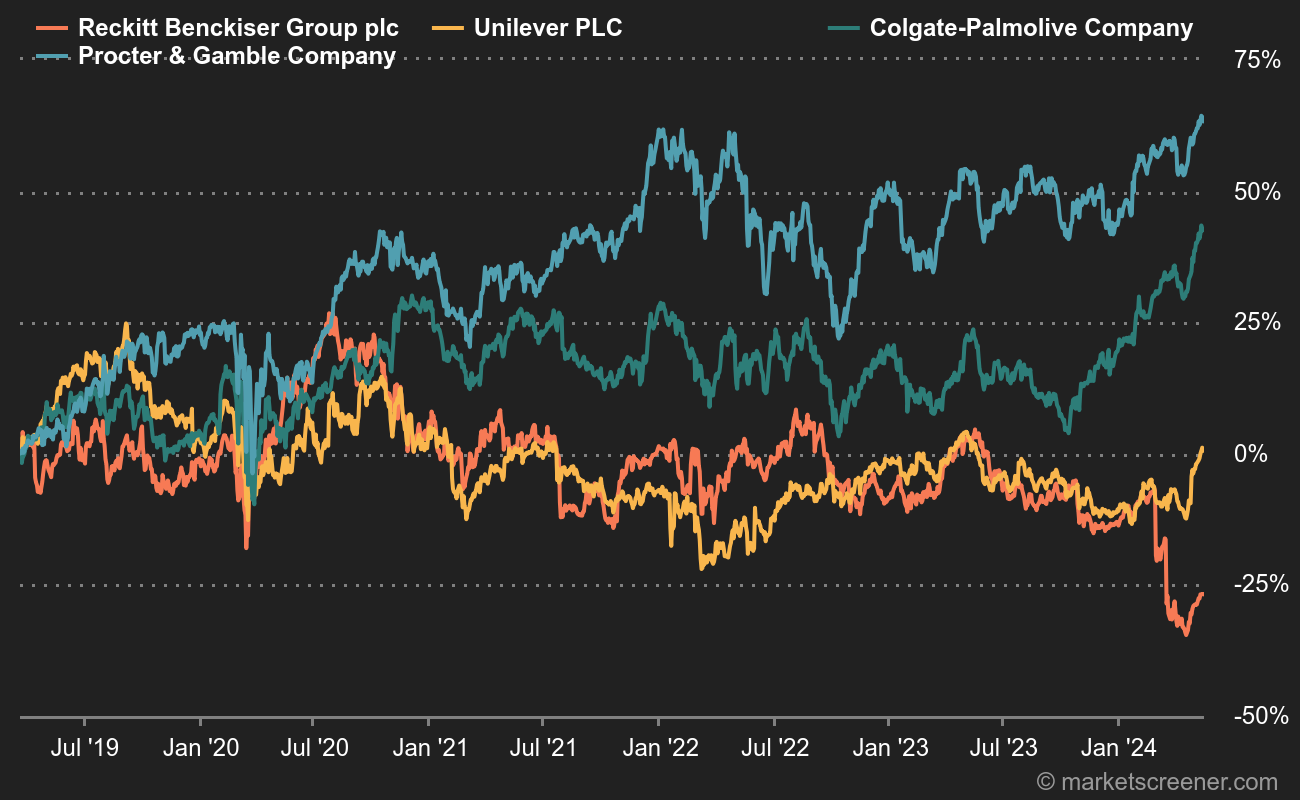

Anglo-Dutch mergers have created powerful multinationals. Royal Dutch Shell, Unilever and Reckitt Benckiser are good examples. The latter is going through a difficult period on the stock market. This has been the case for the last ten years, and even more so over the last five years, when dividend increases have not even enabled the company to match the performance of the FTSE100, even though it has not been the sharpest of the European indices since the Brexit.

A major global player in FMCG

Reckitt Benckiser is the result of a merger between a British company, Reckitt, and a Dutch one, Benckiser, in 1999. Unless you live on the moon, it's almost impossible not to know at least one of the group's brands. For example, Air Wick if you want your toilets to smell of synthetic perfume, Calgon for washing machines, Cilit Bang and Harpic for scouring, Nurofen for headaches, or Woolite if you want soft little sweaters... In short, you see, well-known brands. Reckitt Benckiser posted sales of £14.6 billion last year, employs 40,000 people and has posted an operating margin of over 20% for years. This profitability is rather high for the sector: well above that of Unilever, a little less than Colgate-Palmolive, and on a par with Procter & Gamble. Nonetheless, this margin has tended to erode since peaking in 2016, and Reckitt is lagging behind its peers on the stock market.

Reckitt is at the back of the pack over 5 years

Promises and more promises

This persistent weakness is the consequence of a period of transformation launched in 2016 that hasn't really delivered on its promises so far. In fact, it's fair to say that investors' patience is being sorely tested, as better days have been put off for eight years now. And yet, the perimeter has evolved towards more dynamic and profitable specialties. Well, supposedly more dynamic and profitable.

In 2016, Reckitt generated 33.5% of its revenues from its Healthcare division (Nurofen, Gaviscon, Durex, Strepils, Scholl...). 18.5% came from the Household division (Vanish, Calgon, Air Wick...) and 41% from Hygiene (Harpic, Finish, Veet, Dettol...). The balance (around 7%) came from unclassifiable products, notably in the food sector (mainly mustard and ketchup).

In 2017, the group broke its piggy bank to buy the American Mead Johnson for $16.7 billion and gain a foothold in infant nutrition, a sector full of promise but one in which many reputable groups have broken their teeth.

In 2018, following this transaction, the Group split its operations into two divisions, allocating the assets of its Home division to the other two entities. Healthcare gained weight, up to 62% of revenues, thanks to the contribution of Mead Johnson brands as well as Durex and Veet. Hygiene fell to 38.4%. This organization survived only two years, and Reckitt has returned to a three-division model from 2020: Health, Hygiene and Nutrition.

By 2022, Health Care (42% of group revenues) would have the highest adjusted operating margin: 27.5%. Nutrition (17% of revenues) followed with a 23.1% margin, ahead of Hygiene (41% of revenues) at 20.4%. Margins, as we said, are rather solid for the sector, even if they have tended to erode in recent years. As for the valuation, it's not outrageous: over the last ten years, Reckitt Benckiser paid just over 20 times cash earnings. That's more than Unilever (less profitable) and less than Procter and Colgate (less indebted). According to analysts' projections, the company is valued at less than 15 times expected earnings this year, and around 13 times next year's: that's low!

So what's the problem?

Reckitt Benckiser has simply never really lived up to expectations in recent years. The group struggled to justify the acquisition price of Mead Johnson, then alternated between publications that raised hopes, before disappointing the market. In short, performance has been inconsistent. And when things are going well, there's always a little grain of sand somewhere. The recently published results for Q4 2023 are a case in point. Good growth in the Hygiene division was offset by unexpected underperformance in the other two divisions. To make matters worse, the Group had to reveal that accounting problems had affected two Middle Eastern markets. Not really serious for the finances, but bad for the reputation. To crown it all, the 2024 outlook is rather timid and will rely mainly on the second half of the year. This means that the first part of the year will be mediocre and that we'll have to work hard on the second, which is further away and therefore more uncertain.

However, last week's fall was the result of another cloud on the horizon: an Illinois jury ordered the Mead Johnson subsidiary to pay $60 million to the mother of a premature baby who died of an intestinal disease after being fed Enfamil infant formula. A worrying precedent for the company, which could face further litigation. In fact, there are other infant milk lawsuits underway in the United States. Earlier this week, Reckitt indicated that numerous complaints had been lodged against infant formula manufacturers in general, but explained that it did not know, at this stage, how many concerned its Enfamil.

The share price fell to GBX 4190 last Friday, its lowest level for over ten years. This bout of weakness has brought back to the fore a sea serpent in the market: the demerger of the group. Many experts believe that activists, sniffing the scent of blood, or rather of permanent disappointment, could take advantage of the weak share price to take an equity position and force far-reaching changes.

By

By